Oren Harris of Arkansas

Boston Payola Trial

"This seems to be the American way of

life, which is a wonderful life. It is primarily built on

romance. I'll do for you, what will you do for

me?"

WILD disc jockey Stan Richard

Oren Harris of Arkansas

Nov. 6, 1959

House of Representatives subcommittee members, led by Rep. Oren Harris, announce they are probing commercial bribery in promotion of broadcast music. They received a letter from the American Authors and Composers Guild charging that bribery is a "prime factor in selecting music for broadcasts and that the Federal Communications Commission and the Federal Trade Commission know of this but have failed to act upon it." The following day, the National Disc Jockeys Council denies the Guild's charges through a wire to the committee.

Nov, 17 1959

ABC opens probe of disc jockeys and popular music programs with a special emphasis on Mr. Dick Clark. ABC is satisfied that Clark had never received any personal considerations for playing records or having performers appear.

They order all personnel connected with selecting and playing records to directly divest themselves of financial interests in phonograph recording, music publishing and related fields. Dick Clark says he'll drop all such interests.

Tony Mammarella

A. Mammarella, producer of Clark's American Bandstand, resigns rather than dropping his interests. "I see nothing wrong in a producer playing his own hit record on the show (American Bandstand)."

Nov. 20, 1959

WABC dismisses disc jockey Alan Freed after he refuses to sign a statement that he never got funds or gifts to promote records. He states that the move had nothing to do with payola. Freed reportedly refuses on principle and denies taking bribes.

Nov. 24, 1959

WNEW-TV ends pact by mutual consent and claims that Freed signed an affidavit denying improper practices and said "all station disc jockeys and program directors had also signed affidavits."

Nov. 25, 1959

American Authors and Composers tells the FCC that payola to disc jockeys is merely symptomatic of a larger disease, involving the whole industry's distortion of music programming for its own financial gains.

Nov. 26, 1959

Freed looking over supoena

Alan Freed is subpoenaed when he failed to keep an appointment with Hogan.

Nov. 28, 1959

Freed's financial records are subpoenaed.

Nov. 29, 1959

|

|

Freed admits getting checks from record companies for "consultation," stating "This is not payola."

Nov. 30, 1959

Billboard Magazine reports that the payola scandal "will substantially damage the careers of at least twenty-five dj's." Freed is quoted as saying, "My career has gone down the drain."

Dec. 4, 1959

Recording stars Bobby Darin, Les Paul, Mary Ford and E. Rodgers deny paying to play on Freed's TV show.

Dec. 14, 1959

Billboard is convinced that payola has all but ceased. One Philadelphia distributor complains "You can't even buy the disc jockey's lunch."

Jan. 8, 1960

Burton Lane

American Authors and Composers Guild President Burton Lane kicks off the now decade, charging that broadcasters use $10,000,000 a year to promote the music they control.

Feb. 8, 1960

The House of Representatives opens public hearings on disc jockey payola with dj's from Boston testifying.

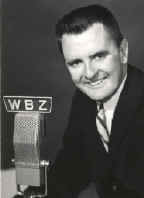

Dave Maynard

WBZ disc jockey Dave Maynard says he received over $6,000 in gifts and cash from Boston record distributing companies for promoting records outside the station but denies it's payola."

Alan Dary

WBZ disc jockey Alan Dary admits he received $400-500 as Christmas gifts but was never paid to plug records.

Norm Prescott

EX-WBZ disc jockey Norm Prescott testifies in a closed session at his own request.

Paul O'Friel

WBZ general manager Paul O'Friel says Maynard and Dary were suspended in November after WBZ probe but were reinstated on probation.

In a 1973 Real Paper supplement, the Ear Book II, a time capsule written by Dave Maynard explained:

"The newspapers used screaming headlines in "war type" (72 point letters). You know, "DJ's Admit Pay." I testified in Washington and after finishing I bought four papers, the Washington Post, the New York Daily News and two Bostonian dailies, and went back to my hotel room. There were four different accounts of my testimony. And the news had me "flashily dressed in a yellow sport jacket and dark glasses. A flashy yellow sport jacket! I've always been an Ivy League dresser and I remember that I was wearing a grey Harris tweed jacket with no sunglasses,"

Feb. 10, 1960

WILD ex-DJ Stan Richard admits his $117.42 clothing bill was paid for at a Miami D.J. convention by record companies. He defends gifts as "America's way of life" (see opening quote) . The quote had Eisenhower in a rage back at the White House

FCC Proposes a law to make payola a crime.

Feb. 15, 1960

Max Richmond

WMEX President Max Richmond testifies he received $14,000 for broadcasting one distributor's record for 13 weeks.

WMEX manager R.S, Richmond says WMEX began announcing payments at the beginning of the probe.

Arnie Ginsburg

WMEX disc jockey Arnie WooWoo Ginsburg announces he received $4,400 in three years from record companies but denies payola charges. Representative Oren Harris is angered.

Feb. 16, 1960

The House subcommittee calculates that Boston disc jockeys received $40,472.54 in three years from four Boston record distributing companies, Music Suppliers, Dumont Distributing, Mutual Distributors and Records Inc.

The investigation reveals interesting interdependencies between two of the companies, Music Suppliers and Dumont Record Distributing. Music Suppliers' Vice President Dinerstein testifies that AM-Par Records' President Sam Clark participated in giving high interest loan to California record manufacturers through Music Suppliers which Clark once headed. Dinerstein said that Music Suppliers pays premiums on Clark's life insurance policy with Music Suppliers' President, H. Carter, as his beneficiary.

Another claim made is that Am-Par paid part of the salary of Music Suppliers' promotion man, H. Weiss, and that payment to disc jockeys is a common practice of courtesy, not payola. Anyway, it is stated, the practice ceased when the probe began.

Dinerstein reports that Carter owns over 50% of Dumont Record Distributors.

Feb 18, 1960

Closed-session testimony from WBZ's Prescott is made public: he reports that from 1950 to 1954, record companies organized a nation-wide ring of disc jockeys who regularly played records for pay. Prescott is the first leading disc jockey to admit getting payola amounting to $9,955.08 from various Boston companies.

Music Suppliers promoter H. Weiss testifies he rigged lists of Top 10 Records using stationery borrowed from Boston radio stations and sent them to the trade publication Cash Box top 10 lists supposedly compiled by disc jockeys. He claims that he did not realize that AM-Par was paying part of his wages.

Feb. 19, 1960

S. H. Clark, in a closed door testimony, makes public that he was to be paid $50,000 over a 20 year period from Music Suppliers, after leaving them in 1955

.

Joe Smith

WILD disc jockey Joe Smith testified that two record companies paid him royalties on records sold in the Boston area, including one record in which Dick Clark had an interest. He also admitted that he had received $8,955 in a three year period from companies and seven manufacturers but denies payola.

Bob Clayton

WHDH-TV disc jockey Bob Clayton denies that artists appeared on his Boston Ballroom show but were not paid. He admits that he received $300 from Music Suppliers.

Dumont Record Distributing head Dan Dumont admits giving disc jockeys $8,565 but denies it was payola.

March 1, 1960

FCC asked four Massachusetts stations (WMEX, WILD, WORL, WHIL) to justify the renewal of their Federal licenses in light of their involvement with payola and gave them 30 days to reply.

March 30, 1960

Thomas "Tip" O'neill

State Rep. Tip O'Neill demands that the FCC investigate all stations whose employees were involved in payola. O'Neill is convinced that the captive audience of American youth must be safeguarded from the demoralizing effects of payola and rock 'n roll ("a type of sensuous music unfit for impressionable minds.")

April 21, 1960

Dick Clark

Dick Clark, described as the single most influential person in the music business, takes the stand on his own behalf. He admits that he had a financial interest in 27% of the records he played on American Bandstand in a 28-month period.

Sen. Oren Harris' reaction?

"You're not the inventor of the system or even its architect. You're a product of it. Obviously, you're a fine young man."

May 20, 1960

Alan Freed is arrested along with seven others for receiving $30,650 in payola from five record companies.

August 30, 1960

WBZ general manager Paul O'Friel says that ex-disc jockey Norm Prescott lied in his February testimony.

Norm Prescott denied these charges.

December 17, 1962

Alan Freed pleads guilty and was slapped with a $300 fine and a six-month suspended sentence.

As should be obvious from Sen. Harris' reaction to Dick Clark's testimony, Clark slipped through the trials virtually unscathed. The price for his transgressions was, nevertheless, high. In the end he had to divest himself of involvement in what turned out be over 33 different businesses!

Alan Freed was blackballed within the business and his career shattered. Freed subsequently fled to Florida where he drank himself to death amid obscurity on January 20, 1965, the day Lyndon B. Johnson was inaugurated. At the time, he was facing tax evasion charges.

We'll take no tearful leavings

We'll say no sad goodbyes

For though our hearts are heavy

The world before us lies.

-From Freed's 1940 high school yearbook

As for all others involved in the trials, they got off pretty much scott free.

Sen. Oren Harris himself was indicted not long after in a conflict of interest scandal unrelated to the music business.

Dave Maynard sums it up best. "The effect of the payola scandal was that the old record promotion techniques were prohibited. Promo men were no longer permitted to talk to jocks. Now the promo man talks to either the music director or the program director and records are judged by committees consisting of the music and program directors and a couple of the jocks. I honestly think that there are far fewer poor records on the air today."

One important thing to remember is that, before the trials, payola was never made illegal. It was a common practice in the music industry. The only problem that drew investigation was that the money wasn't being declared on dj's tax returns.!

When a law was passed during the trials, payola became a federal offense with a sentence of up to one year and a fine up to $10,000.

![]()