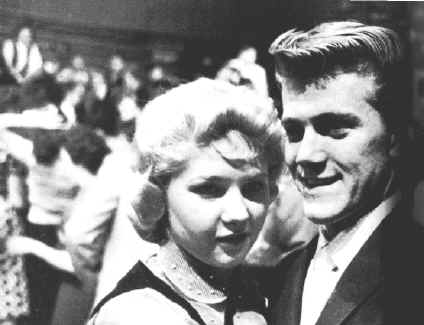

Sitting in the bleachers is one of the most common things a teen does - at football games, track meets, dances, shows and sometimes even at church. They do it at school, in choir and at graduations. Using bleachers on American Bandstand made the set feel familiar. But as regular Arlene Smith remembers, "They were hard and uncomfortable." (from the right first row, fourth and fifth girls) Carmen and Ivette Jimenez watched as Dick interviewed one of his daily guest.

|

|

When Anyone remebers Bandstand or American Bandstand they general think of two things: Dick Clark and the regulars who appeared on the show more than two or three times a week. The egulars here are pictured of-screen, were not actors or professinal dancers, but oridinary high school students. The concept of the regular toke off when Bandstand dancer, Tom DeNoble, appeared at a local dance and more than a thousand kids showed up to see him. No one expected so many people and it was immediately clear to the producers that regulars drew a huge viewing audience, as well as a dependable studio audience. Becoming a regular was a lot easier than most viewers imagined. If viewers knew your name and wrote to you, you could get a membership card. Bunny Gibson remembers getting mail the second week show was on the show and becoming a regular the third. As a regular you didn't have to waiti in line, and. at least in the early days, you could get on the show every day. As the number of regulars increased, the nunber of days they appeared on decreased. Ed Kelly says he was allowed only on the show on certain days of the week. There were about sixty regulars in the fifties, and many viewers could name them all. For teen viewers, especially outside Philadelphia, the regulars were role models. Girls copied hair-dos and make-up; the boys copied dance steps and clothing styles. By the time the show moved to Los Angeles in 1964, where multiple episodes were filmed in one day, the regulars were less important to the dynamic of the show.

Doing

The Stroll

After the American Bandstand teens created the popular dance

called the Bunny Hop, the kids began churning out new dances for

every new beat. Following the Bunny Hop was the Stroll, a slow,

simple dance, where two lines - boys on one side, girls on the

other - faced each other,. They dragged one foot behind the

other, shifting from left to right, then back again. The fun came

when the couple met in the middle to strut down the aisle,

all eyes on them. The dance was inspired by Chuck Willis' hit

"C.C. Rider." It became so popular that Willis was

dubbed "King of the Stroll." But the dance soon got a

song of its own when Dick Clark suggested to the Diamonds that

they create a song specifically for the dance. The Diamonds hot

with their hit "Lil Darlin'" (1957), struck gold again

with "The Stroll".

|

|

|

In the 50s and 60s the last dance at the hops was usually a slow dance. Whether it was the Flamingos crowing Lovers Never Say GoodBye (1959) or Jesse Belvin lamenting Good Night My Love (1956), teenagers grabbed their special partners and slowly circled the floor. Slow dancing was intimate, or as Dick Clark characterized it, "getting sexually aroused with no payoff." Despite the lights and cameras and the fact that six million people were watching, the kids on American Bandstand managed to enter the world of slow dancing.

Fabian

and Family

Fabian was not a singer when he was singled out for stardom, but

Fabian (born Fabiano Forte) studied hard, learning to sing, walk,

talk and act. He spent time at concerts watching other

performers, and it paid off. In 1959, he had three hits,

"Turn Me Lose," "Tiger," and "Hound Dog

Man." Like Avalon, Fabian left Philly for Hollywood. By the

end of the sixties he had made more than a dozen films

Bobby Rydell was born Robert Ridarelli, and was the third of Philly's teen idols. When stardom came for him, he was ready. Recording for Cameo Records, he hit big in 1959 with "Kissin Time." Over the next four years, Rydell had nineteen top twenty hits including the million seller "Volare" (1960), a cover version of Domenico Mogugno's 1958 hit, "Nel Blu Di Pinto Di Blu." Like his friends Fabian and Frankie Avalon, Rydell went to Hollywood. Much of the teen idol's success was because they all lived close to the American Bandstand studio. At a moments notice - when the studio phoned - they could replace a guest who hadn't shown up. Each had a good rapport with Dick Clark, who visited them in their South Philadelphia homes. The surprise was that, despite their fame and fortune, they lived modestly like many of the kids who watched the show.

|

|

After years of glamorous teen rebels, making teen idols was one of the ideas behind the celebrity machine that Chancellor Records created in the late fifties. Two of the chosen boys - Frankie Avalon and Fabian -were white, Italian, likable, easy going teens from the same South Philadelphia neighborhood. Avalon was Chancellor's first success. His initial releases in 1957, "Cupid" and "Teacher's Pet," were bombs. His third release "De De Dinah" (1958), an innocuous ditty that even Avalon had no feel for, sold a million copies, and was the first of six top ten hits. Avalon soon left Philadelphia

|

|

When anyone remembers Bandstand or American Bandstand they generally think of two things: Dick Clark and the regulars that appeared on the show more than two or three times a week. The regulars pictured here off screen were not actors or professional dancers, but ordinary high school students. The concept of the regular took off when bandstand dancer, Tom DeNoble, appeared at a local dance and more than a thousand kids showed up to see him. No one expected so many people, and it was immediately clear to the producers that regulars drew a huge viewing audience, as well as a dependable studio audience. Becoming a regular was a lot easier than most viewers imagined. If viewers knew your name and wrote to you, you could get a membership card. Bunny Gibson remembers getting mail the second week she was on the show and becoming a regular the third. As a regular you didn't have to wait in line, and, at least in the early days, you could get in to the show everyday. as the number of regulars increased, the number of days they appeared decreased. Ed Kelly says he was only allowed on the show only on certain days of the week. There were about sixty regulars in the 50s and many viewers could name them all. For teen viewers, especially outside Philadelphia, the regulars were role models. Girls copied hair-dos and make-up; boys copied dance steps and clothing styles. By the time the show moved to Los Angeles in 1964, where multiple episodes were taped in one day, the regulars were less important to the dynamic of the show.

Justine Carrelli and Bob Clayton

Justine Carelli and Bob Clayton were the dream couple of the

show, the star struck lovers. Justine started dancing on

Bandstand in 1956, when she was still in junior high school. She

spent almost an hour, five days a week, on the fifteen-mile bus

ride from her school to the WFIL studios just to dance.

Meanwhile, in Wilmington, Delaware, a young high school school

student, Bob Clayton, was watching the show and falling in love

with Justine. He made his way to the show in 1957 and asked

Justine to dance. Letters poured in, and Justine and Bob

became the most popular and best known couple on the show. The

couple was on magazine covers, in newspaper articles, and

appeared at scores of dances and shows. In 1960, they added

singing to their partnership, cutting two records.

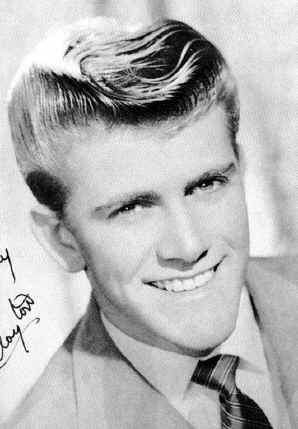

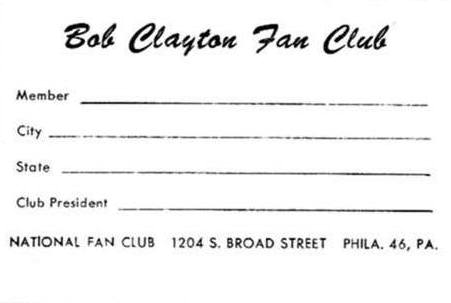

Bob

Clayton Fan Club

The popularity of regulars like Bob Clayton spawned fan clubs

loosely knit organizations dedicated to honoring the lives and

the images of favorite dancers. For less than a dollar, fans got

a member ship card, background information, an autographed

picture, and a periodic newsletter, which kept the fans abreast

of where their favorite regulars would be appearing, what he or

she liked to do for fun, and who was dating whom. Dave Frees, who

heads the American Bandstand Fan Club, remembers when the

president of Carmen Jimenz's fan club went off to college and

offered him the club, he jumped at the opportunity. Over the

years, he picked up the fan clubs to virtually every regular who

appeared on the show during its Philadelphia days. Today he has

over a thousand members in the American Bandstand Fan Club.

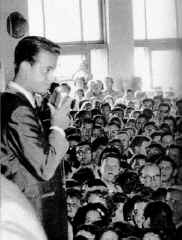

Every

Afternoon

Every afternoon millions of teenagers turned on their television

to watch American Bandstand. Many dreamed of going to

Philadelphia and dancing next to the regulars, but with a studio

that only held about 150 people, it was impossible for most. So

Dick Clark took the Caravan, stars and its music to the teens.

Wherever it went thousands waited in lines for hours to dance and

see Dick Clark in person.

Drawing

Huge Crowds

Marine Ballroom at the Alantic City Steel Pier

The Caravan drew huge crowds of teens. In many of the towns there

were no theaters or auditoriums to play in, so the entourage

often squeezed into locker rooms to change and crowed onto

makeshift stages to perform. By stage time thousands of teens

stood shoulder to shoulder to see Clark host an evening of rock

'n" roll.

Taking

a Bus Trip

A group of fans take a bus trip to New York

for Dick Clark's Saturday Night Show; their legion of fans were

there to greet them.

|

|

|

|

In 1959, Dick Clark put together of first Caravan of Stars, a rock and roll show featuring some of the biggest names in the business, and booked it all over the country. Like Bandstand, Caravan was integrated, a fact that displeased many people, especially when the show went south. The Caravan performers traveled -practically lived - in a cramped uncomfortable bus. Though they weren't glamorous accommodations, the bus was cheap. The performers weren't making much money. The top salary of $1200 went to the headliner. Most other acts earned $500 - $600 a week. Dividing up the fees after expenses left very little. But there were few venues for rock and roll in the late 50s and early sixties, and the performers and promoters took what they could get.

![]()