|

|

|

|

Advertising on American Bandstand

|

|

|

|

With a college degree in advertising and an uncanny ability to speak to teenagers, Dick Clark was the perfect pitchman for sponsors whose products - from shampoo to acne medication to watches - were targeted at the adolescent market. In the late fifties, as the teenage market expanded and the number of teenagers jumped from seven million to twelve million, Clark shifted from local spokesman for Barr's, a popular Philadelphia jewelry store, to a national spokesperson doing endorsements for hair tonic, chewing gum and soda. He helped link up enough sponsors to make American Bandstand one television's most profitable daytime shows

Dance

Contests

![]()

One way to spotlight the songs, the dancers, and the dances on American

Bandstand was to hold dance contests. Kids in the

studio loved them, and the viewers did, too. The rules were

simple. Contestants had to sign up to get a number, then once a

week they pinned numbers on their backs, much like they did in

the dance marathons in the thirties. During the contests, viewers

cast ballots for their favorite dancers. Each contest lasted

three or four weeks, after which winners were announced on the

air. Several of the winners confessed that the voting was done

more on popularity merit. Still, they took their prizes, which

ranged from portable TVs to juke boxes.

|

|

|

|

As audiences for Bandstand grew, so did the stakes for the dance contest winners, who took home prizes that ranged from record albums to brand new cars. Here are pictures of the first-prize, a Ford Sunliner in the Pony contest won by Frani Giordano and Mike Balara.

|

|

|

Dorothy Horner and Frank Spagnoula won the Chalypso Contest in 1957. Paula Kopicko and Richie Cartledge won the 1962 Mashed Potato Contest

Original

Set

Dick Clark inherited the original set for American Bandstand

from Bob Horn's Bandstand, the show Clark took over in

1956. The painted background was that of a record shop of the

late forties or early fifties, when records were big, clunky 78

RPMs. Clark's high podium, like a bandstand, set him apart from

the dancers. The podium was donated to the Smithsonian Institute

in 1981.

Roll

Call

"Joanne seventeen South Philly," "Mark J, fourteen

Bartram High, "Scott fifteen, North Catholic." Roll

Call was a regular feature on American Bandstand and how

the viewers at home got to know the kids on the show. When the

show was only broadcast locally the kids gave the names of their

schools, as well as names and ages. When the show went national

in 1957, they gave their names, ages and their hometown.

Clues

Kids watching American Bandstand at home were looking

for any clues that signaled romance between kids on the show -

who danced with whom, how closely they danced, and how slow they

danced together. In the innocent fifties euphemisms for touching

and sex abounded in the American culture, especially in

television. Harmless games - where kids came into more innocent

contact with each other - spiced up the Bandstand program.

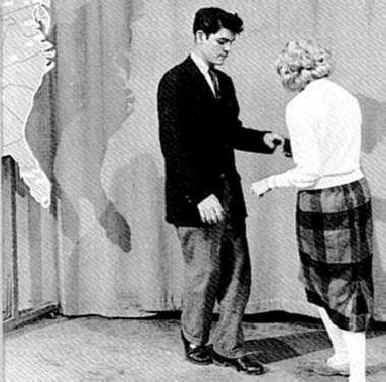

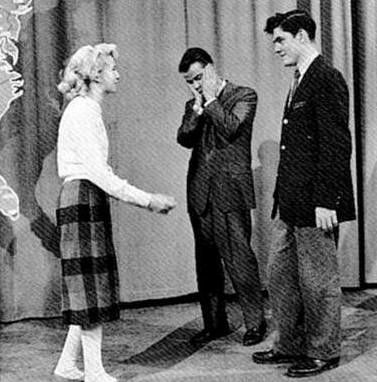

In this awkward moment, teens cooperated to eat up the string

attached to a marshmallow. Of course, if both partners succeeded

they came as close to kissing each other as was possible on a

show that morally towed the line.

Johnny

Mathis

Johnny Mathis signs autographs at the autograph table during his

October 15, 1957 debut on American Bandstand. For teens

who grew up in the late fifties, Mathis was the unchallenged

make-out king, whose silky smooth voice really filled a darkened

room. When Mathis released two singles in 1957, "Wonderful,

Wonderful" and "It's Not For Me To Say," teenagers

had their Frank Sinatra. The following year he had seven hits,

including the classic "Chances Are." His album, Johnny's

Greatest Hits (1958), the first of the greatest hits albums,

remained on the charts a record 490 weeks. Only Pink Floyd's Dark

Side of the Moon (1979) surpassed it.

Rate-A-Record

"It's got a great beat and you can dance to it." Those

immortal words came to represent the most popular feature of American

Bandstand, Record Review. The formula was simple: three kids

listened to three records and rated them between thirty-five and

ninety-eight. A fourth teen calculated the average, often with

the help of Dick Clark. The kids were usually right in their

judgments, picking scores of songs that became top ten winners,

demonstrating once again how their opinions counted.

Getting

Mail

Dick Clark and Frani Giordano

For millions of American teens who could not get to Philadelphia

to meet their favorite regulars in the American Bandstand

studio the next best thing was voting for them in one of the

shows many dance contests. The contests were a regular feature,

giving viewer's a chance to see their favorite couples and the

newest dances. Tens of thousands of fans sent their ballots to

American Bandstand, PO Box 5, PA. In a normal week, the show

received 45,000 letters. During the contests, 150,00 ballots

and letters came in, prompting Clark to joke that all the mail

bags in Philadelphia were being used to carry mail to show.

Halloween

With five shows a week, fifty-two weeks a year the producers of American

Bandstand had to come up with features to keep the show

fresh, interesting, and fun. One way was to celebrate Christmas,

New Year's, and Halloween. the Halloween shows were the most

amusing since they incorporated games, mask, and special guest

stars like the ghoulish Zacherle performing the novelty hit,

"Dinner With Drac " (1958) One of the most popular

games was musical chairs, where the masked teens rushed to find a

seat when the music stopped, and others ended up on the studio

floor. The thin line between childish and teenage behavior

sometimes evaporated with party games that were silly but

made for good fun and more importantly, better TV.

|

|

|

One of the most popular dances created by the Bandstand crowd was the Chalypso, a combination of two popular fifties dances., the Cha-Cha and the Calypso. The simple dance could be done to songs as different as the Shirelle's "Will You Love Me Tomorrow" (19570 and Gene Pitney's "Every Breathe I Take" (1958). When the Chalypso became popular, several songs were written specifically for it; the most successful was Billy and Lillie's "La Dee Dah" (1957). These two dancers demonstrate the steps to Dick Clark.

Dancing

Couples

L-R: Carmen Jimenez,

Frankie Vacca, Norman Kerr, Joyce Shafer, Mike Balara, Frani

Giordano, Dick Clark

Jitterbug Dance Variations

The Jitterbug was one

of the popular dances on American Bandstand. It was demanding,

but it was fun. Here are three couple demonstrarting different

variations of the complex steps.

|

|

For many Americans growing up in the 1950s and early 1960s, American Bandstand was more than just a television show. It was a cultural ritual, a doorway to dreams, and a weekly spark of music, fashion, and youth. When the clock struck four, living rooms across the country lit up with rhythm, and teenagers everywhere kicked off their shoes or laced them tight—ready to dance.

![]()