|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

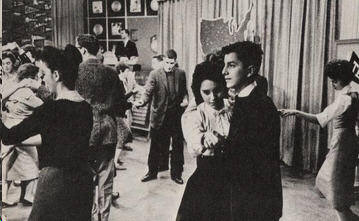

After waiting outside on Market Street in the heat and cold and rain, kids lucky enough to get into American Bandstand were anxious and excited. Walking through the doors to Philadelphia's WFIL-TV's Studio B, where teenage life and music were all important, was like walking into Oz. The light, cameras, and music made the studio a magical place. There was, as with any television show, a lot of illusion. Television was still a relatively new medium in 1957, and studio was crude by today's standards. The cameras and lights were large, bulky, and hard to move, making trick shots of kids dancing virtually impossible. The studio was cold, the lights were hot, the music was loud, and the floor was hard. Girls wore sneakers or flat shoes to save their feet from soreness from the cement floor. But the kids were oblivious to the physical discomfort; they were the stars of the first TV show to feature real teenagers.

Carmella MonteCarlo and Charlie Zamal

American Bandstand was the first national TV show to

feature teens off the street. Carmella MonteCarlo and Charlie

Zamal were two high school students who danced on the show five

times a week. Bandstand dancers were local Philadelphia

kids fourteen to eighteen years old, mostly from two high

schools, West Catholic and South Philadelphia who came to dance

and to be seen dancing every afternoon from 2:30 to 5:00 P.M. It

was after-school fun, way for teenagers to express who they were

and, for a nationwide teen population with nine billion dollars

to spend in allowance money, Bandstand was the showcase

for latest records, the hippest fashions, and the newest products

The teens watching at home finally had a show that they felt part

of, learned from, and measured themselves against. Vera Badamo,

who grew up in Brooklyn Hills in the fifties, remembers how

"wonderful it was to come home everyday and tune in Bandstand

and see Italian kids, just like me. You never saw them on regular

TV. And, to see some of them wearing Catholic school uniforms was

extraordinary. I realized the kids in Philly were just like kids

in Brooklyn."

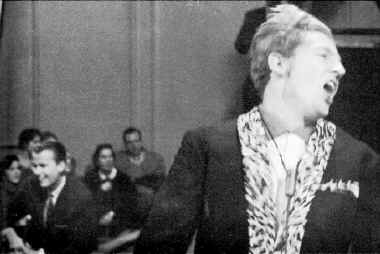

Lou DeSero a Bandstand Regular

Lou DeSero, a teen who appeared on American

Bandstand several times a week was loved for his

slicked-back, pumped up pompadour. In the late fifties,

Philadelphia boys were split on how to wear their hair. South

Philadelphians styled it high and shiny; North Philadelphians,

inspired by TV's Peter Gunn, wore their hair short and to the

side. For guys, tweed jackets, button-down shirts, and thin

patterned ties were the uniform.

Map of

Bandstand Afflilates

When American Bandstand went national on August 5, 1957

it had lined up affiliates on a small network of sixty-seven

stations. A map of the United States in the studio was dotted

with affiliate flags. By the end of the first year the show was

seen in 4,00,000 homes and local stations were clamoring to come

aboard. American Bandstand was much as a neighborhood

dance as it was a national television show. Dancing was an

integral part of the life in Philadelphia, the city that starts

the New Year dancing up Broad Street in the centuries-old

Mummers' Parade. The rest of the year there were dances

everywhere, from St. Alice's School where more than 2,000 teens

gathered on Friday and Sunday nights to the very small VFW dances

in Southwest Philadelphia where twenty people might show up.

Records

Dick Clark's world was records - playing them, producing them,

promoting them, and even pressing them. During the fifties, both

the 45 RPM and rock 'n' roll had a metric rise that would change

popular music forever. Until the, the recorded music was

primarily heard on heavy, awkward, and breakable 78 RPMs. The 45

made the 78 obsolete; it was light, small and practically

indestructible. And because it was cheaper to manufacture, it

gave independent record companies a fighting chance in the

industry. Rock 'n' roll was born with the 45 RPM. Teens could

easily carry the cheap, seven-inch disks to parties.

In 1957, 45s cost 69 cents in Philadelphia, and in many places.,

if you bought six, you got one free. Because Dick moved with the

times, by the end of the decade he owned or had interests in

thirty-three companies associated with the business.

Pat

Molittieri

Dancing in the 1950s was an extension of the pre-war dances,

couples touched; boys led and the girls followed. But within the

prescribed formats, individuality reigned, Pat Molitierri

demonstrates her expertise in Jitterbugging, the most popular

dance on the early Bandstand shows. Each dancer had his or her

particular style of Jitterbugging, but Pat's was the most unique

- she bounced. One of the most popular teens on the show, she had

her own advice columns in several teen magazines

Jitterbugging

When the kids on American Bandstand were not Strolling,

or Twisting, or Chalypsoing, they were usually Jitterbugging. The

Jitterbug was a Philadelphia staple, and there were many

variations as there were Philadelphia neighborhoods. The dance

began in the 1920s in the bars of Harlem and took the steps from

the Shag and the Charleston. Although dancers did wild

improvisational solos as part of the Jitterbug, it was

essentially a partner dance. In 1927, the solos gave rise to a

new variation, the Lindy Hop, named after Charles Lindbergh, who

had just made his historic solo flight across the Atlantic. The

Jitterbug gained wide popularity in the thirties when Swing was

at its peak. During WW II, U.S. soldiers took the dance around

the world and it was recognized as quintessentially American

Barbara

Marcen

Few things are as much fun for teenagers as dancing. It's a

chance to show off and be noticed. For the teens on American

Bandstand like Barbara Marcen, it was a chance to be seen by

millions The dancers, especially the regulars, were always

jostling for a spot in front. "we were brats about it,"

remembers Arlene Sullivan. We wanted to strut our stuff in front

of America," says Bunny Gibson. "But," says Carole

Scaldeferri, "Dick didn't want us hogging the camera."

"he used the studio mike to get us away from the front.

You'd be dancing, and all of a sudden you'd hear Dick's voice

telling you to drop back to the rear," says Kenny Rossi.

Myrna Horowitz says, "Dick wanted to give everyone a chance.

I didn't like dropping back, but I understood it."

Arlene Sullivan and Kenny Rossi

Arlene Sullivan and Kenny Rossi danced together n American

Bandstand for a little more than a year. At the height of

their popularity, they received as many as 500 letters a day.

Arelene, whose mother was a devoted fan, claims she danced on the

show "to get my mother's attention." Within three

months, Arlene was a regular appearing five days a week. "I

was always surprised," she says," that people wanted my

autograph. I danced on a TV show; nothing I did was

different than kids were doing in their basements. But maybe

that's why we were so popular. We were them, and they were

us."

Bandstand's Girl Next Door

Justine Carrelli was American Bandstand's girl next door Always

conservatively dressed and neatly coifed Justine was the girl

that every mother wanted to see her son marry. She first danced

on the show when she was only twelve, two years younger than the

rules allowed, thanks to her sister's birth certificate and

make-up. Justine was an instant hit; in a few weeks she was a

regular. When Justine met Bob Clayton and they started dancing

and dating her popularity soared - the two personified the

innocent lyrics of the songs they danced to.

Danny

and the Juniors

Danny and the Juniors, who appeared on the American Bandstand'

anniversary show in 1958, was a group of four teenaged boys whose

members went to John Bartram High School with some of the show's

regulars. Danny (Rapp) and the Juvenairs sang on the street

corners until Artie Singer of Singular Records heard on of their

songs "Do the Bop." He took them to Dick Clark who,

realizing the Bopwas on its way out as a dance craze, suggested

they change the lyrics. The song got a new title, "At the

Hop"(1957), which over night became a number on hit. The

group's "Rock and Roll Is Here To Stay" (1958) became a

teen anthem later that year

Jerry

Lee Lewis

The first Record played on the premiere network installment of American

Bandstand was Jerry Lee Lewis' call to action, "Whole

Lot of Shakin' Going On". His sharp clothes, animated

performances - Lewis was known for kicking the piano stool from

under him, playing the piano standing up, banging out chords,

rocking from side to side, and wildly tossing his hair -

electrified audiences. The success of "Great Balls of

Fire" sent the dapper singer's career into the stratosphere.

Searching For New Material

With thirty five records to play, the producers of American

Bandstand were constantly searching for new material. Clark

met in his office with representatives of the record industry to

keep apprised of the latest releases and the newest singers and

groups. But in 1959, following the scandalous revelations that

Charles Van Doren had been given answers while a contestant on

the popular TV quiz show Twenty-One (1956-1958) questions were

raised about the honesty of the record industry. Investigators

alleged that deejays accepted bribes to play certain songs,

otherwise there was no way to explain why many rock and roll

songs had become popular. Being the number one deejay in the

country, Clark was called to testify at the 1959-1960

Congressional hearings on payola. He swore he never took money or

gifts, but he was still forced to give up his interests in the

record business

Regulars Wating To Get On The Show

Janet Hamill (seated) waits with the rest of her friends to be

admitted to the WFIL studio.

Christmas |

Hong Kong |

New Year's Eve |

Ice Skating |

Roaring

Twenties |

Halloween |

Western |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

American

Bandstand broadcast special holiday shows for Halloween,

Christmas, and New Year's Eve. There were also theme shows

including a Skating Party, a Hong Kong Party, Roaring 20's Party

and a Western Party at Frontierland.

![]()