Paul Anka |

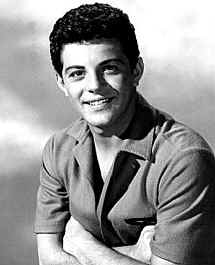

Frankie Avalon |

Freddy Cannon |

Bobby Darin |

Fabian |

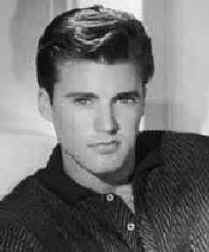

Ricky Nelson |

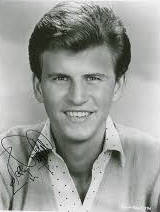

Bobby Rydell |

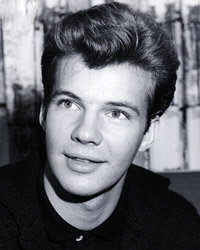

Bobby Vee |

To many avid rock historians, the teen idols --

who were firmly entrenched on the top of the charts between the

death of Buddy Holly and the rise of the Beatles -- represent the

greatest threat to rock's survival that the music ever weathered.

Wimpy, overwhelmingly bland and safe, their connection to rock

& roll was often tenuous, and their commercial ascendancy has

even been discussed as a conspiracy by the music business and

sundry other moral authorities to rob rock & roll of its

vitality.

In retrospect, that seems fairly unlikely, though there's no

doubt that the more conservative elements of the entertainment

industry and the status quo as a whole felt more comfortable with

these performers. Owing as much or more to traditional Tin Pan

Alley and middle-of-the-road values than pure rock & roll,

their massive success nonetheless didn't come close to stamping

out the forces that gave birth to the explosive soul, surf, and

British Invasion sounds that reclaimed the airwaves after only a

few years.

"Teen idols" were by no means a phenomenon that began

with the rock & roll era; bobbysoxers had been pining to the

sound of mainstream pop crooners for a good decade or more before

Elvis hit the scene. As far as rock was concerned, the original

teen idol was Pat Boone, whose first hits were bowdlerized

versions of classic rockers by Little Richard and Fats Domino.

The first two teen idols to achieve mass success after Boone

could hardly have possibly defined the polar extremes of the

genre better. There was Paul Anka, whose early hits were

mainstream ballads with mild rock & roll trimmings, and who

exemplified the style at its most operatic and melodramatic. Then

there was Ricky Nelson, whose success was virtually guaranteed by

his popular weekly TV series, and whose rockabilly records were

better than they had any right to be.

The Philadelphia teen idols of the late '50s -- Bobby Rydell,

Frankie Avalon, and Fabian -- patterned themselves after Anka

much more than Nelson. Recorded on the local Cameo-Parkway,

Chancellor, and Swan labels, they were launched into national

success with regular appearances on American Bandstand, hosted by

Dick Clark, who sometimes held financial interests in the record

companies of the singers he pushed in this manner. Rydell, at

least, could sing; few would contest that Avalon and Fabian were

promoted more on their appearance than their limited vocal

abilities, and both would move into movies and television work as

their chief focus after their initial musical success.

It worked the other way around as well, of course; established

teenage television stars with meager vocal abilities were hustled

into recording studios to capitalize on their screen images.

Ex-Mouseketeer Annette Funicello became one of the first big

female teen idols in this fashion, and Ed "Kookie"

Byrnes, Connie Stevens, Johnny Crawford, James Darren, and

Shelley Fabares also got onto the hit parade after they were

already established TV performers. Artistically, this was the

weakest wing of the teen idol genre; unsuited for singing in the

first place, their material often sank to the level of drivel,

with a few unexpected choice items thrown in, usually from Brill

Building songwriters.

A great many teen idol singers had one or two big hits in this

era without establishing a long recording career. Mark Dinning

(Teen Angel) and Ray Peterson (Tell Laura I Love Her) capitalized

on the short-lived vogue for teen death melodrama; Troy Shondell,

Johnny Tillotson, Brian Hyland, and even a young Tony Orlando

were merely some of the more successful of thelegions of young

faces who were packaged for the young, middle-class, white,

predominantly teenage audience in this era.

Then there were the singers who happened to be packaged as teen

idols, but who were probably good enough to have succeeded

anyway. Dion, Gene Pitney, and Del Shannon, as well as Ricky

Nelson, all fall in this category; their music sometimes

contained the melodramatic hallmarks of the teen idol style, but

they were genuine pop/rock innovators each and every one, and

have too often been dismissed as superfluous by listeners more

concerned with these performers' images than their actual

accomplishments.

And there were also teen idols whose music was obviously a

watered-down version of early rock & roll forms. Bobby Vee

was a transparent Buddy Holly clone, though much softer; Ral

Donner was the most accurate Elvis Presley soundalike, though he

took after Elvis's pop/rock ballads rather than the King's

rockers; and Johnny Burnette had a brief career as a mainstream

teen idol after moderate success as one of the best early

rockabilly singers. Finally, there was an entire wing of British

teen idols, although they had virtually no success in the States.

Cliff Richard was by far the biggest, followed by a stable of

singers with unlikely movie-star names, most managed by British

impresario Larry Parnes. Billy Fury was the best of them; Adam

Faith, John Leyton, Heinz, Helen Shapiro, and others were also

big in their homeland before they largely sank into irrelevance

after the rise of the Beatles in 1963 by......... Richie

Unterberger

Many teen idols of the 1950’s weren’t that much different than the ones today. Popular singers like Frankie Avalon made millions and were able to afford things like fast cars, luxury motor yachts, and mansions.

![]()