Among the first to capitalize on what became

known as blue-eyed soul, The Righteous Brothers achieved their

greatest success in the mid-60s under producer Phil Spector.

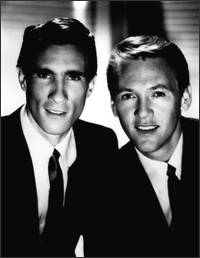

They weren't brothers, but Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield (both born in 1941) were most definitely righteous, defining (and perhaps even inspiring) the term "blue-eyed soul" in the mid-'60s. The White, Southern California duo were an established journeyman doo wop/R&B act before an association with Phil Spector produced one of the most memorable hits of the 1960s, "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'." The collaboration soon fell apart, though, and while the singers had some other excellent hit singles in a similar style, they proved unable to sustain their momentum after just a year or two at the top.

When Medley and Hatfield combined forces in 1962, they emerged from regional groups the Paramours and the Variations; in fact, they kept the Paramours billing for their first single. By 1963, they were calling themselves the Righteous Brothers, Medley taking the low parts with his smoky baritone, Hatfield taking the higher tenor and falsetto lines. For the next couple of years they did quite a few energetic R&B tunes on the Moonglow label that bore similarity to the gospel/soul/rock style of Ray Charles, copping their greatest success with "Little Latin Lupe Lu," which became a garage band favorite covered by Mitch Ryder, the Kingsmen, and others.

Even on the Moonglow recordings, Bill Medley

acted as producer and principal songwriter, but the duo wouldn't

break out nationally until they put themselves at the services of

Phil Spector. Spector gave the wall-of-sound treatment to

"You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'," a grandiose ballad

penned by himself, Barry Mann, and Cynthia Weil. At nearly four

minutes, the song was pushing the limits of what could be played

on radio in the mid-'60s, and some listeners thought they were

hearing a 45

single played at 33 rpm due to Medley's low, blurry lead vocal.

No matter; the song had a power that couldn't be denied, and went

all the way to number one.

The Righteous Brothers had three more big hits in

1965 on Spector's Philles label ("Just Once in My

Life," "Unchained Melody," and "Ebb

Tide"), all employing similar dense orchestral arrangements

and swelling vocal crescendos. Yet the Righteous Brothers-Spector

partnership wasn't a smooth one, and by 1966 the duo had left

Philles for a lucrative deal with Verve. Medley, already an

experienced hand in the producer's booth, reclaimed the

producer's chair, and the Righteous

Brothers had another number one hit with their first Verve

outing, "(You're My) Soul and Inspiration." Its success

must have been a particularly bitter blow for Spector, given that

Medley successfully emulated the wall-of-sound orchestral

ambience of the Righteous Brothers' Philles singles down to the

smallest detail, even employing the same Mann-Weil writing team

that had contributed to "You've Lost That Lovin'

Feelin'."

It's a bit of a mystery as to why the Righteous Brothers never

came close to duplicating that success during the rest of their

tenure at Verve. But they would only have a couple of other Top

40 hits in the 1960s ("He" and "Go Ahead and

Cry," both in 1966), even with the aid of occasional

compositions by the formidable Goffin-King team. In 1968 Medley

left for a solo career; Hatfield, the less talented of the pair

(at least from a songwriting and production standpoint), kept the

Righteous Brothers going with Jimmy Walker (who had been in the

Knickerbockers).

edley had a couple of small hits in the late '60s as a solo act, but unsurprisingly neither "brother" was worth half as much on their own as they were together. In 1974 they reunited and had a number three hit with "Rock and Roll Heaven," a tribute to dead rock stars that some found tacky. A couple of smaller hits followed before Medley retired from performing for five years in 1976; they've toured the oldies circuit off and on in the 1980s and 1990s. -- Richie Unterberger, All-Music Guide

Bobby Hatfield was found dead in his Raddison Hotel dressing November 5, 2003 before a performance in Kalamazoo, Michigan. An autopsy found he had died of advanced coronary disease. A toxicology report in January 2004 found that cocaine use brought on the heart attack but that there was already significant blockage of the coronary arteries.

![]()